clinical trial

A clinical trial, also known as a clinical research study, is a protocol to evaluate the effects and efficacy of experimental medical treatments or behavioral interventions on health outcomes. This type of study gathers data from volunteer human subjects and is typically funded by a medical institution, university or nonprofit group, or by pharmaceutical companies and government agencies.

A typical scenario for a clinical trial is that a patient who is already ill from a disease agrees to undergo experimental treatment in the hopes a new drug or medical device improves his or her condition.

The purpose of a clinical trial is to determine if a new treatment or test -- or a potential drug or medical device -- works and is safe. A clinical trial can determine which medical approach might work best to treat life-threatening diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, coronary heart disease and HIV/AIDS, along with other equally pernicious and debilitating conditions. Potential treatments include drugs, medical devices, vaccines, blood products or gene therapy.

Why clinical trials are important

Clinical trials are important because they improve medical research in terms of usefulness and safety. They teach investigators what does and does not work when analyzing new ways to detect, diagnose and treat disease.

Clinical research can determine whether a drug under review has the desired effect, how the drug is metabolized, how much of the drug should be administered to a patient and how often it should be administered. A clinical trial can also determine what side effects are associated with the drug; how to best manage these side effects; if the drug has any undesirable interactions with food, drink or other drugs; and how these effects can be avoided.

Regulation of clinical trials

In the United States, strict rules for conducting clinical studies have been put in place by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Drugs intended for human use are evaluated by the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) to ensure that the drugs marketed in the U.S. are safe and effective.

Potential treatments must meet acceptable safety standards and demonstrate efficacy before being approved. Therefore, these drugs and treatments undergo a series of phase trials to determine whether the product or protocol can offer benefits and to determine any possible side effects.

Other countries regulate clinical trials according to their local laws, although some -- such as the U.K. -- have rules similar to the U.S. In 2017, China announced new regulations that will affect clinical trials and promote innovation in drug research, according to contract research organization Pharmaceutical Product Development.

Clinical trial phases and how they're defined

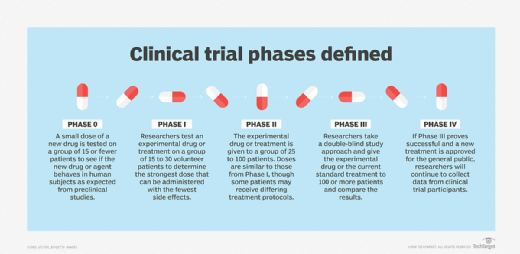

In the U.S., clinical trials are divided into five stages of research.

Phase 0 -- also referred to as Early Phase I. This phase differs significantly from other phases of clinical trials as it is not a required part of testing for a new drug. However, the purpose of this phase is to expedite the drug approval process.

Phase 0 studies, also known as human micro-dosing studies, use only a small dose of the new drug in fewer than 15 patients over a short period of time. The goal is to determine if the new drug or agent behaves in human subjects as is expected based on preclinical studies.

Smaller doses mean less risk to the patient compared to the human subjects in later phase trials, but it can also mean the patient will not see the same benefits, if any, as those in phase II or phase III. In any of the trial phases, treatment can be halted if the side effects present a danger to the patient.

Phase I. Researchers test an experimental drug or treatment with a small group of volunteers, from 15 to 30 patients, to determine the highest dose that can be administered while incurring the fewest side effects. Placebos are not administered during phase I clinical trials, as the goal is to see how the experimental drug interacts with a human subject. If the results look promising, the trial moves to the second phase.

Phase II. During this phase, the experimental drug or treatment is given to a larger group of volunteers, from 25 to 100 patients, to see if it is effective and to further evaluate its safety. While doses of the drug are akin to the levels administered in the first phase of the trial, some phase II participants can be assigned to different treatments groups in which they may receive different treatment protocols. Placebos are not typically used in this phase, either. Again, if the results look promising, the trial will continue to the next phase.

Phase III. Phase III clinical trials compare the safety and effectiveness of the new treatment against the current standard treatment. The experimental study drug or treatment is given to a larger group of volunteers -- 100 or more. Researchers monitor side effects and effectiveness while also comparing the experimental drug to the current standard of treatment.

To do this, researchers often employ a double-blind study approach during which neither the doctors nor the patients know which treatment protocol the patient is receiving -- the new one or the standard one. Human subjects are selected at random and assigned a protocol. The purpose of this kind of study is to eliminate the power of suggestion -- in other words, to eliminate subjective bias from the test results.

Placebos may be used in some phase III studies. If the experimental treatment is found to be effective and can be used safely, it is evaluated and potentially approved for use by the general population.

Phase IV. Once a drug or treatment has been approved for use by the general population, researchers will continue to gather data from the clinical trial participants.

On average, it can take about 10 years for a drug to go from preclinical development to approval in the U.S. The drug development process, from inception to approval, can cost pharmaceutical companies and research firms millions -- and in some cases billions -- of dollars.

Clinical trial vs. clinical study

A clinical study is research conducted with the intent of gaining medical knowledge. Observational and interventional are the two main types of clinical studies. A clinical trial is an interventional study.

In an interventional study, participants are put into groups and receive one or more interventions or treatments, a placebo -- or sugar pill, or no intervention. Participants receive specific treatment according to the research plan or protocol the researchers created.

Human subjects who volunteer to participate in these types of studies may receive diagnostic, therapeutic or other types of interventions. Researchers can then evaluate the effects of the assigned course of treatment on biomedical or health-related factors.

These interventions can include drugs, therapeutic agents, prophylactic agents, diagnostic agents, medical devices, procedures, vaccines and noninvasive approaches, such as modifying diet and exercise.

One example of an interventional study is a randomized control trial (RCT). During a randomized control trial, human subjects are chosen at random to receive an intervention. Generally, participants are arbitrarily placed into one of two groups: the experimental group receiving the intervention that is being tested, and a comparison group, or control group, which is receiving the standard practice of care, a placebo or no intervention at all. The goal of a randomized control trial is to quantitatively measure and compare the results following the interventions.

Observational studies differ from interventional studies in that, while participants may receive diagnostic, therapeutic or other types of interventions, researchers do not assign participants a specific course of treatment. Observational studies look to understand cause-and-effect relationships, drawing inferences from a sample group where variables are not under the control of the researchers.

Eliminating bias in clinical trials

Clinical trials are created to answer specific questions, and they often overlap. For example, a university trial may seek answers on how to detect a particular illness, while a government agency trial about the same illness might seek answers on how to prevent the illness from occurring. A pharmaceutical company's study may seek answers on how to treat the illness, while a medical institution's study might seek answers on how to prevent the illness from reoccurring.

Various strategies help to eliminate bias in clinical trials. One example is the use of comparison groups, in which one group receives the current standard treatment for a condition and another receives an experimental treatment. To eliminate bias, patients are randomly assigned to comparison groups. Additionally, the results of each group can be analyzed side-by-side, and no study participants are left without treatment.

Another way to avoid bias is masking, or blinding, which involves not telling the trial participants which treatment they will receive. Researchers may also be unaware of this information, although it can be made accessible in an emergency.